In its efforts to promote contemporary Syrian art and encourage its study, Atassi Foundation will bring you news and reviews on exhibitions and events worldwide that involve Syrian artists. If you wish to contribute to this feature, please write to us on info@atassifoundation.com or shireen@atassifoundation.com.

Here, curator Shulamit Bruckstein writes about Ali Kaaf’s recent solo exhibition, Die Byzantinische Ecke ('the Byzantine Corner') which opened at C&K Gallery in Berlin on 21 April, and runs until 26 May.

“In my imagination, I see the Damascus of my childhood, with its large market and the Grand Mosque. The Mosque was not only there for prayer; it also served as a kind of refuge from the hustle and bustle of the market, offering silence, tranquility, beauty and contemplation, especially in its corners. These corners had a significance of their own: the main prayer was held in the heart of the Mosque, and when it was over the congregation would disperse into these many niches. These were places where you were on your own and could allow thoughts to linger on. It was quiet there; every corner was different, and there was something poetic and meditative about each of them.”

This is what the artist Ali Kaaf told me when I asked him what significance corners had for him. We then delved into philological references: corner, in Biblical Hebrew, is pina, a word that is derived from liphnot, meaning to turn or turn around. It is also the root of the word panim, or ‘face’, i.e. that which turns towards, turns around, or turns away—the Eternal One, for instance, speaks panim el panim (face to face) with his prophet. Also liphnim (inside) is derived from the same root and refers to what has turned inward. Panui, on the other hand, which also shares this root, means ‘empty’ or ‘free for something’.

Indeed, Aramaic commentators, who are usually close to the Hebrew roots, rendered the biblical pina into Assyrian, and translated it via the Aramaic sowita, which is Arabic sawia. In the corners of the great Umayyad Mosque of Cordoba, where the Arab philosophers of the 13th century were wont to teach, whole universities were founded. Even cathedrals, the artist tells me, were built there, each of them a universe of its own.

But what, then, is a Byzantine Corner? For Kaaf, it is the corner where “everything is in flux,” where the architecture reveals who came first and who came second; when and how (and by whom) the Mosque or Cathedral was conquered, overbuilt or reshaped. European conquerors would have demolished or obliterated anything indicative of what they had defeated. In Byzantium, on the other hand, heterogenic elements were allowed to intertwine with one another, forming translucent, transparent layers that resulted in an architecture of ‘both/and,’ with eyeholes allowing glimpses into, and from, the depths of time.

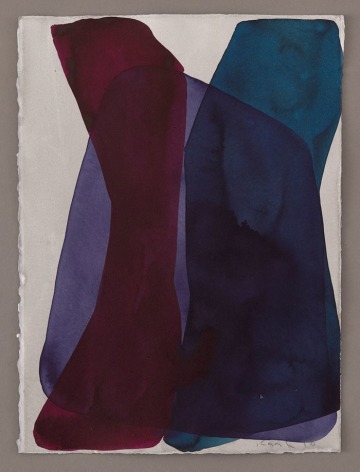

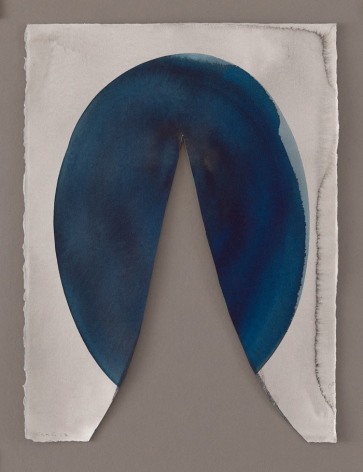

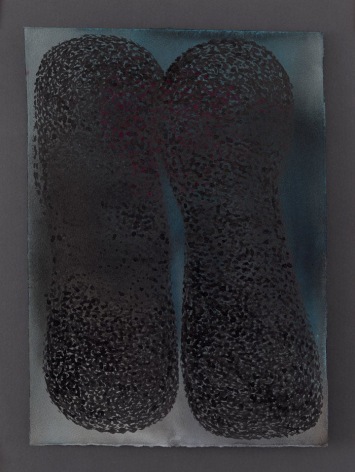

What emerged here, instead of subsequent partitions, is a kind of architectural whisper: the Cathedral of Holy Wisdom, Hagia Sophia, today silently transmits the forms and rhythms of its builders into the wide open space of the Mosque, into the museum that it is today. Ali Kaaf is receptive to this whisper. In his new editions of the Byzantine Corner he uses flowing gestures and photo-cut techniques to explore the overlapping elements, variations, sense of scale, overwritings and deformations of the materials, often showing processes of disappearance that are at work both in architecture and in the psyche. Notwithstanding the many cuts, superimposed layers, and only partially-recognisable forms, he never loses sight of the geometry of the ornament, the details of a Roman tile, the lavish forms of the Byzantine capitals, and the subtleties of the marble.

The photo montages shown in Byzantine Corner are modeled after digital ‘originals’ of architectural details of corners and pillars which the artist made during a visit to Hagia Sophia in Istanbul. The artist digitally overwrites and overdraws these photos; he adds shadows and layers, which, on high-quality paper prints assume the quality of drawings. The photomontages, sliced with broad knife cuts, are enlarged versions of these models and scaled up to different sizes, minimally varied and recut in a photographic process. The size of each individual ‘copy’ is the result of meticulous research, in the process of which hundreds of variations are discarded, with only a few passing the artist’s critical examination. In this playful procedure, which is infinitely variable at any point, the artist cuts, overlays, distorts, works with perspective and creates digital post-processings onto the originals, until each individual piece, each constellation has received its proper size. In this, the lines drawn by the body and the play of the flowing knife cuts are moments of utmost lightness and freedom. Kaaf's photo montages put the limits of photography as an art form to the test: they neither show or document anything. Gesturally, graphically and sculpturally they are independent of, and liberated from, the task of representation; they remind us of the whispers overheard in the Byzantine corner, of its permeability for the flow of form and matter, light and shadow, presence and absence. Kaaf intensely evokes what is missing. With extreme precision he marks and obscures his objects with holes of nothingness that veil their faces.

In Ali Kaaf's works, we recognize Surrealist and Dadaist techniques, oscillating somewhere between dream world, cubist cutting techniques and abstract seriality. Others use photography to question the relationship of perception and documentation; by contrast, Kaaf's photomontages witness geometric shapes, proportions, poetry and body gestures taking on a life of their own. Subject matter, documentation and even the architecture of the Byzantine corner eventually disappear only to recur radically changed by imagination, poetry and movement.

What did Maurice Blanchot say with respect to photography? It presents facts without context, going beyond that which reveals itself; it makes things disappear; it shows us mundane reality in the guise of unpredictable surprise.

Almút Sh. Bruckstein, April 2018

Translation: Christoph Nöthlings

Edited: Anna Wallace-Thompson